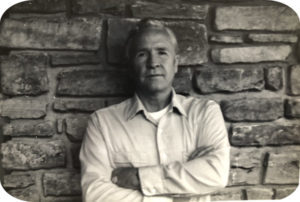

This story was told to me by the man who lived it, Darrow Doyle Faubus, named for the famous attorney Clarence Darrow. During his retirement Doyle became a singer and songwriter in the Fayetteville area. I was lucky to meet him once at the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale, Arkansas. An auditor and farmer, Doyle died in 2018 at 92.

He was the youngest brother of the famous Governor Orval E. Faubus. One of the most mesmerizing Ozark biographies of an Ozark figure is by the late Roy Reed about the governor, who believed one of his greatest accomplishments was supporting the Buffalo River’s inclusion in the National Park system. Orval ended his career as manager of the Dogpatch USA theme park just north from where he grew up. The park went bankrupt in 1993, but recently has been purchased by Johnny Morris, founder of the Bass Pro Shops. Good for Dogpatch!

Like thousands of others during the Great Depression, the Faubus family, with three sons and four daughters, struggled to keep everyone fed. Selling a load of hand-hewn railway ties could put lots of food on the table. I never was able to do a formal interview with Doyle, this is my reconstruction from his memory.

Doyle Faubus lived with his folks way up the White River near the little town of Combs in the wilds of the Boston Mountains of west-central Arkansas. Doyle had graduated from eighth grade in early December during the late 1930s, the roughest time during the Great Depression. Doyle was a boy becoming a man.

That was as far as most country kids went in school those days. Doyle was 14 years old when he finished eighth grade.

On a cold winter night a neighbor came by the Faubus’ breezy old cabin to ask Doyle if he’d haul a dozen ties down from Flat Ridge Mountain. The neighbor had hacked them a month ago. They talked standing in front of the fireplace, turning to warm themselves as his Dad listened.

The 12 ties would be worth $3 at Pettigrew store, that’s $.25 apiece. Out of that Doyle could keep a $1 for doing the hauling. His Dad said he could use their pair of mules and wooden wagon for free to do the hauling. Doyle said he’d do the job, his first since graduating. He was glad for the work. A dollar a day was not bad wages for a 14-year-old in hard times. Not bad one bit for a young man in 1939.

So at 6 the next morning Doyle got up from his bed. He had slept under Old Heavy, the warmest quilt in the house, and noticed snow had drifted under the back room door. Just a little, not enough to get worried. He had the team hitched up and drove out the farm yard in the frigid early light. The ground was froze solid but his last piece of cornbread was still a little warm. The road went past Greasy Creek School where they had just had the graduation celebration. Then the road followed uphill on the icy gravel track.

By 10 a.m. he had the wagon waiting in a clearing near the mountain top with the two mules hitched to the tongs so he could skid those 200 lb. oak ties out of the brush where they been cut and left to dry. Just before noon dinner time he had found all dozen ties and wrestled them into the wagon. It was hard work for a teenager, but Doyle knew how to wrestle an oak railroad tie. He had done it many a time with his Dad and brothers.

Doyle enjoyed a bacon grease and cabbage sandwich, then started down the trail. It was warming up. The ice in the ditches was starting to melt, so he had to be careful to keep up on the high part of the road. All of a sudden he felt the wagon slide a little and fall into a hole. Then there was a sucking noise and he felt the mules pull hard. Finally, a loud ‘snap’. The wagon stopped dead. The rear axle had broken in still frozen mud. Doyle at first didn’t know what to do.

He could look across the valley from where the wagon sat stuck and see a neighbor’s farm way across on the other ridge. The smoke from the chimney looked cozy & warm. Then he knew what he had to do.

It was early afternoon when he got his team unhitched and rode the two mules a mile across over to this other farm.

“You can use our wagon for the day for a half-dollar,” the neighbor said. More than fair Doyle said.

The sun was dipping down by 2 p.m. when he finally reached where his father’s wagon had broken down, drove up around it and backed down so he could more easily load the 12 ties into the borrowed wagon. Together they weighed maybe 3,000 lb. Snow was starting to fall again.

When Doyle backed the neighbor’s wagon around then started down the trail the sun had fallen behind the ridge. The ditches were freezing. Doyle went as slow as he could; he couldn’t break down.

Dark had nearly fallen when he left the Greasy Creek road and got on the main state highway along White River. He had to go slow onto the side of the highway; the team might slip on the icy pavement. Finally he got to the Pettigrew general store. A kerosene light was still on. The owner had stayed open late for him.

Doyle thanked him for waiting. He was glad to get that $1 for delivering the load of ties. Luckily he had brought along a little sack of corn to feed the mules something at the end of their long day. He remembered what his Father said: “Take your time to take care of your animals, and they’ll take care of you.”

Just a few days before he’d been out hunting with his Dad and shot a squirrel. His old hunting dog was so hungry that he didn’t bring the squirrel back like he had always done before. The dog ran into the bushes to eat that squirrel. His family had to have cornmeal mush again for dinner that night, almost like going hungry. His Father was very embarrassed his favorite dog had been so hungry.

So Doyle was extra careful to take care of those mules he had left tied up by the hitching post. He brushed the snow away from the frozen grass to pour out the shelled corn. Down by the hitching post he noticed a little scrap of green paper covered with ice and snow. It was a dollar bill. Doyle brushed the ice off the money and took it back into the general store.

“Some of them old drunk tie hackers must have dropped the note when they were in here earlier today,” the owner said. “Why don’t you keep it? You found it!”

Doyle said he appreciated that. The extra dollar would go to repair the rear axle on his father’s wagon and also help pay for use of the neighbor’s wagon. He should be able to give his mother some of that one dollar the neighbor had promised him out of the $3 for hauling down the load of ties. Doyle said it had been a good day to end up with a piece of luck like that. He was glad to help unload the wagon and be on his way before night and snow made the road hard to follow.

He only had to drive the wagon a few miles along the highway to get back to his family’s cabin up from the river. Doyle didn’t mind the snow. His luck had been good on one of his first days after being graduated from the Greasy Creek School.

*** Featured Image from The Rural Missourian archive